ESC - Spain - Mulhacén

, 3479m - Info | Trip Report | VR Tour

Trip Report :

This report is that of my first ascent in 1999. In 2022 I returned to retrace my steps with a more satisfying alternative start and finish point, and to take 30 photos for a VR Tour.

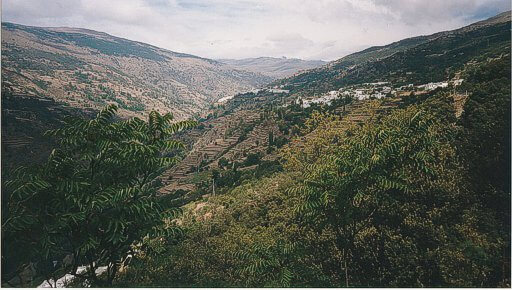

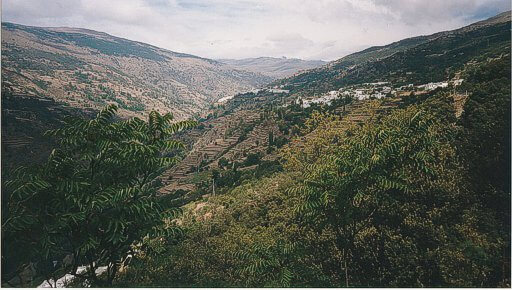

Monday 27th September 1999 seven am, having spent a restless night tossing and turning in the guest house bed, I decided it was good as time as any to get up and make ready for the day ahead. I was slightly apprehensive, the dangers of hiking alone in unknown mountainous country were not lost on me. The Lonely Planet guide to Trekking in Spain, whilst encouraging one to explore the mountains, had done it's best to sow the seeds of doubt. Yesterday, when I had arrived in Capileria (1436 m) by bus from Granada, I had explored the locality, looking for the paths the guide described in it's tour of Las Alpujarras. I had been unable to find them nor those few indicated on the map. I had gone to bed that night unsure of my route; should I make the trek to Travélez, supposedly the highest village in Spain, and make my ascent from there, following a dubious route along trails, acequia (water channels), and compass bearings, or make my ascent of Mulhacén directly from Capileria, from where one could follow forest's edge and jeep track to around 2700 metres, then pick up a smaller hiker's path to the summit? I chose the latter, I did not want to get lost.

|

|

The white washed village of Capileira nestled on the slopes of Les Alpujarras.

|

At eight am, when I stepped out from the guest house, it was still dark. The village children ran down to the water tap and bus tuning point to catch their ride to school, in the narrow street the bus finished it's precision manoeuvre and trundled out of sight, it was quiet, and no one was about. I could have departed then, but I treasured my honour, the bill for the night's bed had not been settled, and besides, they still had my passport. The landlord took his time in attending to me as he strolled about the empty bar and restaurant switching on lights, cappuccino machine, and all assortments of items at completely opposite ends of the premises so that he had to zigzag back and forth. Words of encouragement were out of the question for he spoke not a word of English. I ordered my bill and an orange juice with the minimum of words with the maximum dose of Spanish accent I could muster. I downed the drink, paid quickly, and passport safely stowed away, made my way back out into the streets.

The road wound it's way out of the village and up to the crest of a ridge where it continued, as a rocky track, to zigzag up until reaching a small forest hut at around 2400 metres. I did my best to avoid this section of highway, choosing instead a number of paths that in the first instance formed a tour of the neighbouring hillside, then later the boundary of a coniferous forest that reached up to the aforementioned hut. The ascent was strenuous, though nothing in the least technically difficult, my only burden the twenty kilo sack on my back. I carried with me enough food for four full days (though I intended only three), a change of clothes, sleeping bag, and cook set, but no tent or sleeping mat as I intended to make use of the mountain huts described in my guide. I was even hoping that the stove and food would be unnecessary, and that my meals would instead be cooked by hut wardens; meaty stews pasta and cakes, not the dehydrated soya that I carried.

I rested regularly, sipping my water, nibbling at my food, thankful that though the sun shone, it was not painfully hot. At 1,950 metres the sound of running water caught my attention, I filled up from the acequia and drunk my fill before continuing on. By the time I reached the bunker like forest hut at 2400 metres, clouds had began to form over the summit of Mulhacén and it's neighbouring peeks, I knew I should not be seeing it again. The trek from the hut along the jeep track to the point where it veered from the ridge, was long and drawn out. At the place my map indicated the walker's path to the summit, still seven kilometres further, stood a sign, I cannot read Spanish, but it was obvious from the few words that shared a common heritage, that the path was closed, closed in order that environment reclaim the scar caused by a thousand trampling feet. Thoughtful of the environment, I followed the jeep track a further two hundred metres before turning to my right and making a bid for the summit ridge in order to regain the path further along it's course. In the patchy cloud I passed a total of three walkers, a pair and a solo walker, all on their descent, all with day sacks. I stopped and spoke with the latter for half a minute, having discerned an American accent in his greeting. He had walked up from a mountain hut that morning, failed to summit the mountain due to a pulled ligament, and was now on his way down. He moved on before saying more, yet succeeded in raising my hopes of a manned mountain hut where I could purchase a cooked meal and possibly a beer or glass of wine to accompany it. I struggled on, thirsty now, having drunk all my water, hungry, yet unable focus on the benefits of chocolate, high calories, instant energy boost, great taste. But that is where the chocolate thing went wrong. On the plane from England it must have frozen in the cargo hold, during the previous day's journey by bus, it must have melted, only to solidify again today. It tasted bland, almost powdery, every lump that I swallowed was forced down, and now I had no appetite.

|

|

Shrine on the summit of Mulhacén (3479m).

|

It was close to six o'clock when I arrived at the wind torn summit of Mulhacén, highest mountain in Spain. Through the cloud I could see the large cross and tiny shrine to the Virgin Mary. I spoke a few congratulatory words to myself, took the obligatory photo with aid of timer, and sought out the route of my decent, a faint path down a steep, four hundred metre scree slope on the west face of the mountain. At the bottom of the scree I was back on the jeep track, and four kilometres along this winding trail, Refugio Felix Mendez, hidden from view behind a spur in the ridge and the drifting cloud. Images of the hut and it's warm hearth beckoned, luring me on. I needed the encouragement, having walked more than twenty kilometres and climbed two thousand meters, I was exhausted. I tempted myself with choices from the menu as I forced myself on, passed a small unmanned hut at Terreras Azules at the point where the track rounded the spur, and head on gently down hill to the site of the Refugio Felix Mendez. The site was all I found, a level platform in the rocks about Lagunas de Rio Sece. There was no mistake, I was definitely in the correct location, one could see the trails descending from the track to the lakes, and if to confirm it, the ground was covered in broken brick and tiles. Okay, the Lonely Planet guide was nine years old, but my map, my map was only a year in print. Steak, chips and wine was suddenly off the menu, Raven's spaghetti bog was back on.

Had I a tent I would have stayed put. Had I had water, I would have stopped back at Terreras Azules, but I did not. From the Lagunas de Rio Sece, I filled my two sigg bottles, popped in purifying tablets, and made my return the refuge at Terraras Azules. I had the hut to myself that night, I was able to spread out, and as baptisms go (never before had I slept in a mountain hut), I consider myself blessed. The dark single room was furnished with two pine sleeping platforms, one above the other, a pine topped table constructed from a plinth of rocks, and benches built in a similar manner. The carpentry appeared new, the wooden surfaces clean and polished, shame there were no mattresses.

|

|

The Refuge Pillavientos at Terraras Azules.

|

I cooked dinner (for cooked dinner read boiled water) on my MSR multi-fuel stove, currently fuelled by unleaded petrol hurriedly purchased the day before from a petrol station four kilometres below Capileira, and a kilometre or two above the picturesque village Pampaneira to where I had eventually walked. Working by torch-light, I removed the boiling water from the stove, poured myself a cup-a-soup, followed by the Spaghetti Bolognese. Having forced down all that was hot, I conjured up a chocolate instant whip made with powdered milk, and there I faltered. The first spoonfuls tasted good, yet despite this, every mouthful there after was an effort, the activity of the day having left my stomach too tight to eat in comfort. Worn out by the efforts of eating, I neglected the washing up and made my bed on the top platform. Gathering all my spare clothes, I portioned them into those for my pillow, and those to lay inside a plastic survival bag to cushion my back asI slept. I read for a while, "Galilee" a novel by Clive Barker, and eventually decided on sleep at around ten. Shortly after came a crash, my head hit the pine platform, and I lay dazed in the darkness wondering what had happened. Once awake, there was no great mystery, my pillow, having slid during nocturnal tossing and turning, had disappeared over the side of the platform and struck my unpacked stove with an accuracy I could not have achieved had I tried. The only remaining question was could I retrieved my pillow without leaving the warmth of the sleeping bag? I leaned dangerously over the precipice, stretching to reach the soft bundle, then just as I was about to slide forwards and follow my possessions onto the floor, I decided to brave the cold.

Tuesday 28th September 1999, not an early start, and one made later by my stopping at the site of the non-existent Felix Mendez hut for breakfast and water. It was past ten by the time I regained the jeep track and truly on my way to the next summit of the ridge, Veleta (3,396 m). In distance there was not far to go, the way was not steep, yet it took around an hour and a half to reach the Veleta Pass where the rocky jeep track descended wiser and older in a tarmacadam blanket. Here I was offered my first view towards the north, it was not very nice, brown sandy hills for as far as the eye could see, a desert like world broken up here and there by the roofs of towns and villages. And of course, there were the ski lifts. The road had encouraged day trippers from Granada, in my quest for the wind blown summit I was not alone, and I found it difficult to keep up with their hurried pace, my weighty sack gave me no allowance.

My route from the Veleta Pass to the summit of Veleta itself took a direct line, over a kilometre in distance, across rocky terrain close to the cliff edge from where I could see, far below, the jeep track up which I had recently trod. There was also an easier route to the summit, the tarmacadam road from the pass led up as well as down, and it was on this road walked the tourist against whom I engaged in my secret race.

|

|

Refugio de la Carihuela with the peak of Pico del Veleta (3398m) in the background.

|

Following my decent from Veleta, I stood at the pass an hour later wondering nervously about the next section of my route. The Servicio Geográfico del Ejército map showed no path, the Lonely Planet trekking guide was furnished with the disclaimer; "Accordingly the route description to the Refugio del Caballo is second-hand and cannot be relied on absolutely". I felt like a man about to step out into unexplored territory in search of King Solomon's Mines, his only guide a tattered hand drawn map, and the letter of a mad man informing his wife of his journey.

I found traces of a path leading in approximately the right direction, it was by far the narrowest path I had followed on the entire journey. Piled stones aided my navigation as the path first twisted one way then another, rounding a minor peak before crossing screw slopes and traversing exposed ledges until it once again gained the ridge at a small col. The cairns were not the easiest to follow, did the trail descend from the col down the other side of the mountain, did it turn back, taking a line beneath the crest of La Virgen (3161 m)? After much scouting, I realised the path did neither of these, my route was to scramble along La Virgen's northern flank, gradually ascending to it's narrow summit further along the ridge. Had it not been for the weight of my backpack, I would have enjoyed the scrambling, it was not difficult, simply exposed in one or two places quickly crossed. Once upon La Virgen, the white crested roof of the Albergue del Elorrieta popped in and out of view from behind various rises in the ridge. It's position appeared stunning, perched on the cliff top, dark windows looking out over the southern Sierras. Interestingly, the map gave no true indication of the steepness of the terrain after a certain point, certainly there were no symbols indicating crags and cliffs, both of these elements being in abundance here. The "path" continued on towards the Elorrieta hut, now a target, a talisman that on passing would indicate success and the passing of the most difficult section of the walk.

|

|

Crossing La Virgen.

|

The ridge line dived and rose, passing as it did so great stacks of fractured rock, I negotiated these with speed, dropping down below the ridge line where the ascent would have entailed the rock climbing skills of the like I did not possess. The descents invariably necessitated the crossing of huge boulder fields where dark gaps threatened to devour the unaware, this was not the place to loose balance, and I was glad to put the last of the car size block behind me and scramble, firstly up the scree, then later, up easy crags to the ridge once more.

My guide book described the building at Elorrieta as "A spartan affair with places for 20 persons." In reality the building is much larger, and only if one replaced the word spartan with ruinous would I give the description any credence. It is not the place one would choose to stop for the night, for the floor is covered with much debris from the ceiling and walls that a night spent in it's confines would invite such a stoning usually reserved for heretics of a biblical age. Satisfied that this was indeed the Elorrieta refuge, and not another, I continued on my gentle descent to the Caballo hut, concerned now at what I might find there.

|

|

Ruins of the Albergue del Elorrieta.

|

At the Elorrieta hut, the main east-west ridge of the sierra divides into three. Between the first and second the Lanjaron river is formed at the head of a gentle valley whose side wall quickly steepend as height is lost. My guide book described a path leading to the Caballo hut that hugged the north-western side of the valley and not losing much height. The map too showed this path, and on the ground it was plan to follow, I was gladdened, I had approximately four hours to walk the six or seven kilometres to my place of refuge before dark, and I felt this target was easily manageable. From near the source of the Lahjaron river I filled my water bottles and drank my thirst, topping up my energy also with a few mouthfuls of dried fruit, chocolate, and cereal bar. As the path continued along the valley side, the drop below began to equal that of the cliffs above me, but the path remained constant, even built up in places with walls of nearly a metre where the ground dropped away into murky mires. Perhaps this narrow track was once a miner's path, it's levelness suggesting that it was built with more than human feet in mind. My confidence grew, if the worst was to happen, the cloud to come down, I would certainly not be getting lost.

Then, just as I thought nothing could be easier, the path came to an abrupt end. I could see where the trail re-started, it was perhaps only two metres away, but between myself and it, a great gash in the mountainside cut away the wheat from the chaff, the ardent adventurer from the Sunday rambler. The gap was protected by a wire rope, initially suspended at both ends and centre by iron pitons hammered into the rock, but now hanging free at my feet so that only half the traverse was guarded. I scrambled across, and once having done so decided that it really was not that scary after all. In retrospect, once I had learnt that the Spanish word tajo translated into gorge, I would have been prepared for the Tajos Altos, and perhaps the Tajos de la Virgen earlier that afternoon.

There on, the route imposed a strict order of frustrating, height losing descents and tiring ascents that left me wondering if I had not been better off following the line of the ridge above me. The Refugio El Caballo is situated on a slight rise above a small tarn, Laguna del Caballo, which in turn is situated in a corrie one hundred and fifty metres below the peek of Mt. Caballo (3,011 m). An ascent of the summit via a scree slope to the north looked a satisfying way to start my last day, tomorrow. It also gave the impression of an easy descent had I opted for the high level route along the ridge top. But more concerning was the pile of rocks I spied from a distance that barricaded the door to the refuge. On closer inspection I was relieved to find that what I believed to be a door was in fact a window, and that the metal door was at the opposite end to the tunnel like bunker. Unlike the hut of the previous night, this refuge was bare of furniture, unless one included the roughly rectangular rocks that had been collected for the purpose of seating. In one corner stood a litter infested fire hearth, a channel in the stone worn leading up to a chimney. It was here that I found a note, written first in English, then repeated in a language I guess was Spanish, it read

"In this very nice house there lives a mouse, sleep well."

|

|

The Refugio El Caballo.

|

During dinner, another soya based meal I found particularly tasty, I pondered over the genuineness of the note's claim. Would I be attacked in the night, my eyes scratched out, infected with some fatal rodent carried decease? Would my kit survive? My food broken into? I tried to put the fear out of my mind, concerned myself with more domestic duties such as washing up and bed making, searching for all that I had to separate me from the hard stone floor. I read by torch light, a dog eared candle stub burning at the far side of the room to banish as many shadows as possible.

It was then that I first set eyes on the Beast of Caballo, more the size of a small rat than that of a mouse, it scurried from it's home in the fire hearth; evidently the beast ate well high up here in this barren world of sand, stone and rock. Under the spot light of my torch beam, it fled back into it's home where I intended to make sure it stayed for the duration of the night. I found enough stones to block up the holes in the fire place, and returned to my reading. Whenever I awoke during the night, and I awoke many times lying on that cold, unforgiving floor, I heard the sounds of the beast attempting to escape from his prison, and now that I had him trapped, I decided that the mouse ought to have a name. By torch light, I scanned the graffiti on the hut's ceiling, a calendar of names and dates. Of all, Fidel was written the largest, he had visited sometime during 1989 if I remember correctly, so with no political pun intended, I named the captive rodent.

Wednesday 29th September 1999. From inside the hut, with door closed, it was impossible to tell if it was light or dark outside, sunny or cloudy. During the early hours great gales had rushed passed my mountain eyrie causing me to postpone my getting up for as long as I could bare in fear that the weather outside had taken a turn for the worst. Fortunately the day was as bright and as clear as those that had gone before, I would be in need of the sun cream again.

As planned, I climbed the scree slope to the crest of the ridge then picked my way along a cairned path to the triangulation pillar at Caballo's summit. The view was magnificent and I was not alone to enjoy it for numerous herds of wild goat grazed on the gentler, northern slopes of the ridge. I had witness a number of the animals all along the walk, in areas away from human habitation, but the glimpses had been brief, the deer like animals being quick to flee. Here that wild goats appeared to take comfort in their number and lingered until I was almost upon them.

|

|

View northeast from Pico El Caballo (3011m) twoards Pico del Veleta (3398m) and Mulhacen (3479m).

|

From the summit of Caballo there was no path to follow, but few obstructions either, just a undulating landscape of grass, scree and boulders. For a kilometre I was happy to walk upon the sky line, yet when a path a short distance below me, the continuation of that which led to the hut, came into view, I decided to take it. Exactly how I was to exit this mountain world, pass through the forests and middle heights to reach the small town of Lanjaron at 700 metres, I was yet unsure, though confident a way would be found, that way would be easier found if I began on a path. I was right, the route of my descent was easy to find, after several kilometres on the path it joined an acequia, which in turn joined a forest track. As on my ascent, I followed the forest's edge, a wide corridor of bulldozed soil that lead quickly and steeply to the first road and homesteads. It was not the most exciting way end to the walk, the climax had definitely been yesterdays traverse of La Virgen, but at Lanjaron I arrived early afternoon, satisfied with my adventure in the Sierra Nevada.