ESC - Poland -

Rysy

, 2499m - Info | Trip ReportHigh Tatra Day 1 (Beauties and the Beast) :

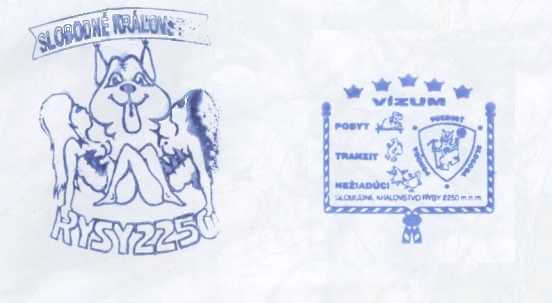

July 2004 Sometimes it is difficult to pick a theme when summing up a hike. Sometimes something unexpected happens and you have it right away. At first I was going to call this "Babes in the Wood", but there was a severe lack of trees, at least in the initial stages of the journey. Then came "Beauties and the Beast" and this was more appropriate. The rubber ink stamp at Chata pod Rysmi, used either as a souvenir or control token to imprint evidence of passage, has the image of a wolf clutching two naked ladies. I asked the bikini clad Slavic beauty behind the hut's service counter what this image symbolised. Her explanation needed some imagination, The slopes of Rysy, she told me, from a certain vantage point, has the same silhouette as the image on the stamp. I fear that this was clutching at straws.

Stamps at Chata Pod Rysmi.

|

| Schronisko przy Morskim Oku. |

Anyway, I have digressed from the well marked path of mountain literature, and should wind back the clock to the day's dawn. It should have been raining, but the forecast was wrong and the storm seemed to have exhausted itself in the night. Thus I awoke around five to clear skies outside the window of the pension. Only problem was that I was on the wrong side of the mountain, in the wrong country in fact. The pension was in Stari Smokovic, Slovakia, on the southern side of the High Tatra, and I wanted to make my ascent of Poland's highest peak from Poland. An ascent from Poland is also the more interesting, with two beautiful mirror like lakes, and a lengthy scramble protected in parts by chains. It took a while to get ready, ask around the for the bus station, realize I had missed the first bus by ten minutes and waited another forty for the next to Lysa polana just a few yards from the Polish border. The journey took around an hour. I crossed the bridge over the Biatka River on foot and passed through the customs post. It was a little unclear what was to come next so I changed ten pounds into Polish Zloty and hitched a lift in the direction of Morskim Oku, Poland's most beautiful lake (if the tourist literature is to be believed). The ride lasted less than a kilometre before we turned into a large car park at the trail head. I paid the 4.40 zloty national park entrance fee (my 10 GBP had yielded me 60 zloty) and immediately spent another 30 zloty to ride the horse drawn wagon (with fifteen others) from the park's entrance at Palenice Biatczanska the eight kilometres to a site fifteen minutes walk from the lake. The wagon ride took an hour and thus I guess saved me fifty minutes off of an otherwise dull plod up the metallised road through forest with all but the occasional view. By the time I struck out from the incredibly busy mountain hotel on Morskim Oku's northern shore, it was 9:30. It took a further forty minutes to reach the lake's southern end and ascend to the second lake with a height gain of around two hundred metres.

|

| Morskim Oku & Rysy. |

Fording the shallow stream that flowed via a waterfall into the lower lake, my ignorance of the local mountain dress code lured me into a false sense of solitude. Thus far the pathway had been well paved, surely the fashion set intended only to trek as far as this second lake (Czarny Staw pod Rysami). It was unthinkable to a walker who had grown up with a Blacks or Millets on every high street, that these people intended to tackle the steep snow field at the tarn's end. Surely it was simply a matter of time before I would be walking alone, have the mountains to myself. But I was wrong and pleasantly surprised.

|

| Czarny Staw pod Rysami. |

The ascent from the second tarn was a tiring climb with little let up in gradient. There was a path of sorts, but often it had been destroyed by land slide or lost from sight in a maze of boulders and gullies. Finding the way-marked route once again was always a relief as a safe line would have been impossible to determine from the map. I was never entirely sure which peek on the jagged horizon was the one I was aiming for, and the way between myself and the silhouette above was often obscured by the convex slope or aforementioned geography.

|

| On the ascent of Rysy. |

As the summit neared, the red and white painted way markers led up a narrow rocky rib with mild exposure. The gradient never ventured into climbers territory, but steel rope protection was on offer neither the less. Here progress slowed until suitable passing places were reached. And there it was the roof of Poland, suddenly only a few metres and one or two interesting steps away. The sun was still shining, though lower peaks to the west were strung with cloud, and I realised how lucky I was. Only twelve hours previous I had gone to sleep beneath torrential rain clouds with the promise of the same for the following day. The weather gods had been on my side.

There still remained the issue of the descent. Until recently it had been illegal to cross between Poland and Slovakia here in the mountains. My guide book spoke of zealous border patrols. Much had changed with the entry of both into the EU.

Once down off the summit cone, the path became a series of zigzags to a Tibetan like landscape of cairns; narrow piles of stones, rock stacked upon rock, yet absent of pray flags. In turn, the path changed bearing and headed across a concave snow slope to the Chata pod Rysmi, meaning Refuge below Rysy, and now of infamous fame. The Slavic website for the Tatra National Park had read that the hut had been damaged in rock fall and was now closed. Thus I was surprised to find it open, ventured inside to investigate and was glad to have done so. The Chata pod Rysmi is a small mountain refuge serving hot meals, snacks and drinks alongside souvenirs. The atmosphere was friendly, and inclusive; being there, climbing Rysy did not make you special, one of the elite, a feeling I had experienced at other alpine refuges. Instead this could have been Ryker's Cafe pod Box Hill, Surrey. Whether this was purely because of the mountain's lower altitude or the nature of the people I do not know. I would favour the latter.

|

| Snowy descent to Chata Pod Rysmi. |

Leaving Chata pod Rysmi was like leaving the mountain behind. Whilst there was some kilometres to go before I ventured from the barren rocks and reached the scrubland of the high valley floor, it seamed that the mountain was behind me. A broad path cut through the thickening pine forest of the Mengusovska Valley, and before long I arrived at one of civilisation's outposts. Popradské Pleso was bustling with day trippers, families and the more serious hiker, the lakeside bars and restaurants making a brisk trade. A tarmac road connected the lake to the lower valley, and it would have been easy to assume that somewhere around there must be a car park. But this was far from the case. Access via the road is only permissible to those who work at the restaurants or delivered supplies. Everyone else had walked here, at least two and half kilometres up hill.

|

| Looking down upon the Mengusovka Valley. |

From Propradské Pleso there were a number options. My original plan had been to trek eastward to the Sliezsky Dom from where I would begin my ascent of Gerlachovský Štít the following day. However I had agreed to meet my guide for that excursion in Stari Smokovic. This factor, and the steep climb up Ostrva on the other side of the lake caused me to reconsider. Of the two remaining routes, I chose the woodland trail to Strbske Pleso rather than the tarmac road. Beneath this final lake, I boarded a train on the ultra-modern Tatra Mountain Railway, and took one final look up into the mountains just in case I could make out the silhouette of a wolf and two maidens....

|

| Chata Propradské Pleso. |